[Henri Labrouste. Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. 1854–75. View of the reading room. © Georges Fessy]

About a week ago I visited the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) to check out the exhibition Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light, on display in the third floor's special exhibition's gallery until June 24, 2013. The exhibition has received a good deal of attention since it opened in early March, most notably by Michael Kimmelman at the New York Times. Below are some photos I took and some of my impressions on the show, though readers in need of a bit more depth on the exhibition should read Kimmelman's piece.

[Photos by John Hill, unless noted otherwise]

MoMA bills the show as "the first solo exhibition of Labrouste’s work in the United States." It took long enough, considering that Labrouste died in 1875. It's not for lack of importance or influence, since the architect's two main projects (really, what he is only known for by most)—the Bibliothèque Ste.-Geneviève and the Bibliothèque Nationale, both in Paris—were seen as precursors of 20th-century modernism by the likes of Sigfried Giedion in MoMA's early days.

The exhibition is curated by MoMA's Barry Bergdoll, with Corinne Bélier of the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine and Marc Le Coeur of the Bibliothèque Nationale, where it was first displayed. Given its location in the third floor galleries, the first impression of the show is not a positive one—visitors must traverse a narrow, linear (and often crowded) gallery that leads to the larger spaces beyond. This first section (above) is being given extra weight by Bergdoll, through his assertion that Labrouste's early restoration studies of Paestum, Italy, "shook up academic dogma," as he says in the exhibition catalog. The many drawings (and Labrouste's drawing instruments, a nice treat) in the corridor are worth beholding, but they create an arterial clog of sorts in the exhibition that is not relieved until moving through the glass doors at the other end. (The photo of the corridor, above, was taken on my way out, in a slow moment.)

While the beautiful photos of the two libraries (on top of this post and below my exhibition photos) are the primary means by which the exhibition is being shared in the media, the show is predominantly drawings and a few models. The drawings—many of them watercolors—are astounding, illustrating Labrouste's skill as a delineator but also his thorough working out of details, from stone decoration to structural ironwork to the insertion of modern services into the library. And one of the show's main statements is that Labrouste is an early Modern (with a capital M) architect, due to his use of modern materials (iron, concrete) and systems and the way in which his libraries defined the modern institution.

The framing of Labrouste as an early modern architect doesn't necessarily come to the fore in the first of the larger exhibition spaces, pictured above. Drawings are displayed on retro, pseudo-drafting tables. The legs made of wood spheres are a bit goofy, but the surfaces make for comfortable viewing of drawings and even videos (visible in the foreground of the photo above). The post-modern nature of the tables comes across in the fact that many of the drawings do not rest on the rails at the bottom of each table; they are mounted above.

Some more historical allusions come in the portal at the beginning of the exhibition and another in a wall separating two of the larger galleries; one side shows his libraries and the other side displays projects of successors influenced by Labrouste. The photo above is looking toward the latter, as if the stacks (the same sort of structural system used at the New York Public Library that Norman Foster and NYPL want to remove) are the most modern aspect of Labrouste's libraries.

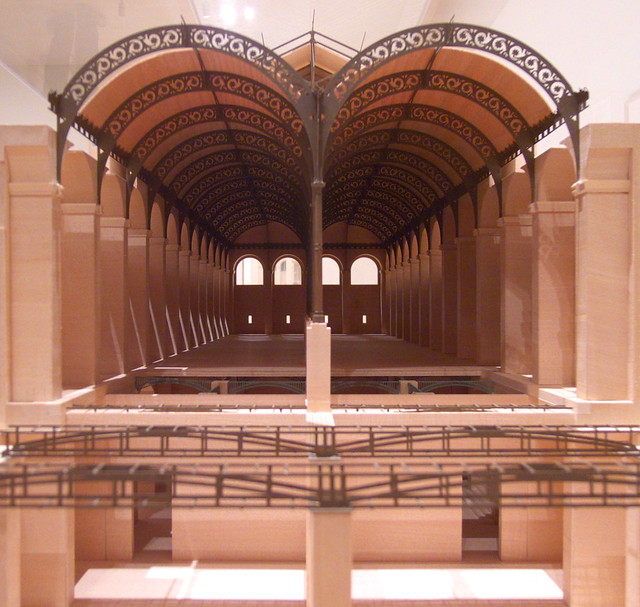

[Model of Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève]

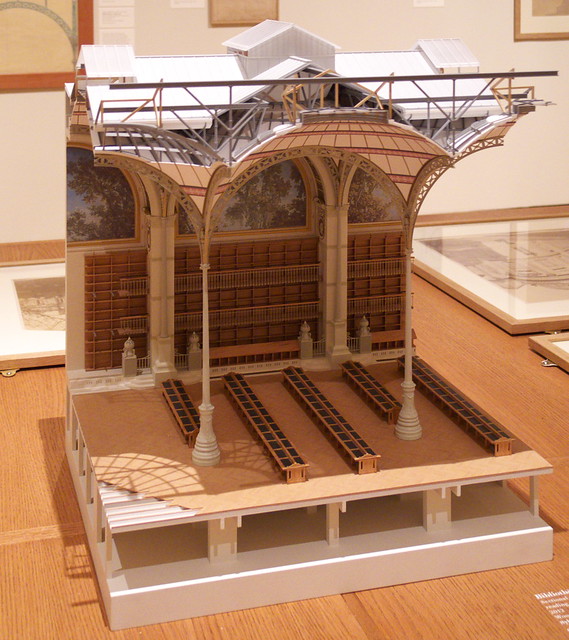

To be honest, I always have a hard time keeping the Bibliothèque Ste.-Geneviève and the Bibliothèque Nationale straight. Their designs are quite different, even though they are both grand spaces structured in iron and light—one is a long vaulted space and one is made up of a series of skylit vaults. But remembering which is which has always been hard for me, though don't ask me why. The exhibition will help refresh my learning from undergrad, but of course the value of the show goes well beyond something like this.

[Model of Bibliothèque Nationale]

When I visited MoMA to see the exhibition I ran into a couple professors from my alma mater, Kansas State University. They were part of a school trip that took third-year students from the Little Apple to the Big Apple; many of their students were taking in the Labrouste exhibition as we spoke. In hindsight the exhibition is perfect for students: It illustrates a sort of "everything is contemporary at some time" aspect to Labrouste's architecture, while also driving home the importance of hand drawing in conveying ideas and exploring design and construction. The latter may be an increasingly archaic notion, but divorcing hand drawing from architecture doesn't seem right to me.

[Model of Bibliothèque Nationale]

The models are also valuable artifacts for students to see. Sure, they were made much later than Labrouste's drawings, but they do an excellent job of showing the various conditions (structure, services, systems) that are behind and below the surfaces that have rightfully attracted so much attention over the years.

For those really interested in Labrouste's libraries, MoMA is hosting (with Columbia GSAPP) a symposium on Thursday: Read: Revisiting Labrouste in the Digital Age. Participants include Barry Bergdoll, Alberto Kalach, Dominique Perrault, Anthony Vidler, and many others.

[Henri Labrouste. Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. 1854–75. View of the reading room. © Georges Fessy]

[Henri Labrouste. Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. 1854–75. View of the reading room. © Georges Fessy]

[Henri Labrouste. Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. 1854–75. View of the reading room. © Georges Fessy]

[Henri Labrouste. Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. 1854–75. View of the reading room. © Georges Fessy]

[Henri Labrouste (French, 1801-1875). Imaginary reconstruction of an ancient city. Perspective view. Date unknown. Graphite, pen, ink and watercolor on paper. Académie d’Architecture, Paris]

[Henri Labrouste (1801-1875). Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris, 1838-1850. Southwest corner: elevation and section. Late 1850. Pen, ink, graphite, wash and watercolor on paper. Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris]

Advertisement

You have just read the article News for today's that category by title Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light. You can bookmark this page with a URL http://news-these-days.blogspot.com/2013/03/henri-labrouste-structure-brought-to.html. Thank you!

Posted by: Tukiyooo

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light Updated at :

3:00 PM

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

Post a Comment